Barber and two protesters

North Carolina's decline from what the editorial board of the New York Times refers to as "a beacon of farsightedness in the South, an exception in a region of poor education, intolerance and tightfistedness" to something unrecognizable to those of us who live here -- particularly those of us, like myself, whose families have been here for generations -- has been swift and putative. I attended last week's protest, spurred, finally, by the House's swift and sneaky passage of HB 695, a bill that contains provisions that will (again, among other things) effectively shut down all but one abortion clinic in the entire state. The presentation of this bill, which is ostensibly about protecting North Carolina citizens from Sharia law, was so underhanded that even our Republican governor Pat McCrory decried the covert nature of its passage.

From Asheville, where I live, Raleigh is about a four hour drive. Along with about 100 other people, including three other faculty members at Western Carolina University, I rode to the rally on one of two buses chartered by Asheville City Council member Cecil Bothwell. Some of my fellow travelers had done this before; some, like the 79-year-old man who shared his story, had been arrested and were wearing their "I was arrested with Rev. Barber" pins in solidarity. Many told their stories of entering the Legislative Building, of their meetings with various members of NC's general assembly, including Tim Moffitt, who represents Buncombe County, and of their expectations for this particular rally.

Seriously.

We brought our own lunches and ate at a rest area about two hours out, and we arrived in Raleigh at about 3.30 with enough time to wander the halls of the legislature prior to gathering on the mall. One of my colleagues tracked down Moffitt and spent about an hour in his office. Later, when we outside, my colleague told me several things about this meeting. Two seem important to me. First, Moffitt said that he was "troubled" that state employees would be in attendance at these events. The implication, as far as I can tell, is that as a state employee, one is not in a position to challenge the state. And I think that there is some real fear on the part of state employees that they could get in trouble for attending such a protest. Indeed, Art Pope's Civitas Institute maintains a database of information about Moral Monday protesters, including, when the institute can get it -- which it can in the case of state employees -- information about protesters' jobs and their salaries (so when you click the link for "protester salaries," you see lots of college professors. I'm not up there, by the way; the database only seems to contain folks who got arrested, which I didn't).

The second thing that Moffitt said to my colleague was this: "you are not those people," meaning the people protesting on the mall. OK, so let me back up for a second. To address the issue of what it means to be protesting as a state employee, none of my colleagues were there to protest as representatives of the state institution for which we work; we were there as individual citizens with individual interests. In terms of not being "those people," my guess is that the reason Moffitt said this to my colleague is that my colleague, like Moffitt, is a young, affluent, white man (Moffitt also asked my colleague how much money he made, and my colleague told him, even as he said that he wasn't attending this rally to protest his pay). "Those people" are, effectively, the NAACP (therefore, black people), women, the poor, and the elderly. At least this is Moffitt's estimation of who "those people" are.

A little protester photographed by another of my colleagues

What's scary -- and very telling -- to me about Moffitt's claim is the very clear indication that Moffitt is dividing his constituents into two categories: people who are "like him," and "those people" who aren't. Such a reality points to a lack of any sort of empathetic imagination that might allow for someone like Moffitt, or for that matter any number of his colleagues in the general assembly, I would venture, to imagine their existences as linked to the existences of the people that they supposedly represent. It's terrifying to know that the North Carolina legislature is a space wherein my district's elected representative can proclaim such blatant racism, sexism, and classism even as the state's citizenry stand outside his window and try to shine a light on that very reality.

When my colleague told me about his exchange with Moffitt, I bristled, and I offered (as I always do as an ecofeminist) that oppressions are linked, intersectional, and co-dependently reinforcing. To see oppressions as discrete entities and to view oppression of one group as somehow independent of the oppression of others is to misunderstand the mechanism of oppression; to claim that those who are being oppressed are not the same people as those who are elected to represent them is to misunderstand the concept of democracy.

Yeah.

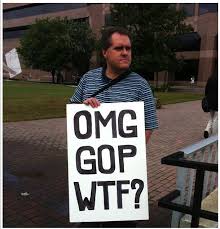

I imagine (and even know after conversations with many folks on the mall) that the people protesting get it, know that what affects one of us affects us all. That's why they were out there holding posters, pumping fists, chanting, and clapping.

On the way back to Asheville, we stopped to get something to eat. It was 9 p.m., and everyone was starved. We pulled into Burlington and stopped in a shopping center where the options were Wendy's, Burger King, Pizza Hut, and Subway. We were told to get off the bus, grab some food to bring with us, so that we could get back to Asheville. When everyone piled back on, they brought with them burgers and pepperoni pizza, turkey subs and chicken filet sandwiches.

The recognition of the interconnectedness of oppressions often breaks down when it comes to animals, even among people who see and recognize such intersectionality as profoundly significant and even as immoral (hence the notion of "Moral" Mondays) when to comes to legislation that affects their fellow human beings. The question that I'm always left with in such instances, when empathy and moral consideration don't extend beyond our non-human framework, is whether or not any liberation movement will ever amount to much when the most liberated and liberal among us fail to recognize as foundational the linkages between animal and human oppressions.

Human beings have justified the oppression of other human beings by rhetorically constructing them as animals. Racism and sexism are predicated on a foundational lack of recognition of "others" as human; consider, as I've noted before, that the Nazis killed the Jews with rat poison, that women are treated "like pieces of meat," that African slaves were sold at auction as chattle.

Oh, and here's an Obama sock monkey.

Don't get me wrong, here: I am behind the Moral Monday movement. I am glad to see the swell of this tide of discontent, the coming together of disparate groups, and the disenfranchasing of the notion that, in issues that pertain to our moral health, there are no "those people" and "these people." But if this movement is about unity and the uniting of what might otherwise be disparate elements of society, then I want for the protesters to consider one more moral issue, and let's have a Meatless Moral Monday. I know you're laughing, but it couldn't hurt, after all. And it might make even more manifest the false dualisms that underscore someone like Moffitt's ability to turn away from all of those voices on the mall. "Forward together." All of us this time.